Four impressive (and supremely cool) ICA teens active in this week’s Teen Convening share their experiences working with the ICA, finding themselves, making art + meeting Whoopi Goldberg. These teens have got it going on.

Jill Medvedow, Ellen Matilda Poss Director of the ICA, has been known to say that the ICA Teens are the heart and soul of the institution. The members of the ICA Teen Council work on site several times a week for years, and their faces are as familiar around the offices as those of the staff. Students in the Fast Forward program may spend more after-school time here than anywhere else.

Their engagement with the ICA combines hard work (organizing huge events), artist encounters (meeting or making art with artists, choreographers, authors, and musicians), creative projects (making films), and amazing opportunities (meeting Michelle Obama, Whoopi Goldberg, and Harvey Weinstein at the White House).

This week, four standout ICA teens will take active roles in the 8th annual National Convening for Teens in the Arts , the ICA’s groundbreaking opportunity for teens from around the country to gather and work toward increasing and improving teens’ role in museum settings, serving as emcees and moderating panels. We asked each of them to share their thoughts on the Convening and some of their most memorable experiences with the ICA.

Name: Amireh

Hometown/neighborhood: Cambridge, MA

School: Homeschooler

Plans for after graduation: To take advantage of the possibilities

This year’s Convening is called After the Bell, and is about alternative spaces that contribute to teens’ education. How has the ICA contributed to your education? What does this space mean to you? What can teens get from spaces like the ICA that they might not get in school?

The ICA is a great reminder of how I can learn outside a traditional classroom. We never have homework or tests when we’re at the ICA, but I still learn a lot. Having the experience to lead tours in the galleries, plan events, and give formal presentations in front of large audiences has helped me to develop skills not often taught in school.

What can young people stand to gain from regular exposure to making, seeing, and talking about art?

When we spend time in the galleries with Teen Arts Council or museum visitors, the conversations we have are always different. Spending time engaging with art, whether it be making art, seeing art, or talking about it, opens up new ideas and possibilities.

Spending time engaging with art, whether it be making art, seeing art, or talking about it, opens up new ideas and possibilities.

What are you most excited about for this year’s Teen Convening?

Since I also attended last year’s Teen Convening, I know that there are so many exciting things to look forward to. However, my favorite part is seeing all the presentations the different museums give. It’s interesting to know what other teen programs are doing across the country and to be able to use it as inspiration for our own events.

What is the weirdest or most memorable thing you’ve ever done at the ICA?

On the Teen Arts Council everyone jokes about living at the ICA, but for one night this past year we all did! Having a sleepover at the ICA is definitely the most memorable and weirdest thing I have done at the ICA. It was also a perfect ending to our Teen Arts Council meetings for the year.

Name: Beatrice

Neighborhood: Jamaica Plain

School: Boston Latin Academy

Plans for after graduation: Going to the Philippines for a month, camp counseling for two weeks, then college.

This year’s Convening is called After the Bell, and is about alternative spaces that contribute to teens’ education. How has the ICA contributed to your education? What does this space mean to you? What can teens get from spaces like the ICA that they might not get in school?

The ICA’s year-long film program, Fast Forward, has been the only source of art education in my high school career. My creativity now has a constructive home to manifest in, thanks to the support of museum educators who are passionate about film and work to make class a safe space. My life isn’t separate from my work when I’m in the ICA, so after the bell on Friday afternoons I go to class in the museum’s digital studio and I feel like I can really be myself and share my ideas.

What can young people stand to gain from regular exposure to making, seeing, and talking about art?

Art can challenge, affirm, and open up the thoughts of a young person who is viewing it. Art is a way of being exposed to experiences other than one’s own that the viewer would normally not have access to. Young art viewers can make connections and learn about themselves while seeing the work of others.

Art is a way of being exposed to experiences other than one’s own that the viewer would normally not have access to.

What are you most excited about for this year’s Teen Convening?

I’m so excited to meet the other teen museum representatives in person! I’m kind of obsessed with them already from just talking with them on the online forums leading up to the conference… I hope they have fun at Teen Night.

What is the weirdest or most memorable thing you’ve ever done at the ICA?

Another Fast Forward student asked me to act in his film… I did it and it was cool to see how other people shoot their films, but at the screening it was so strange and cringe-inducing watching my moving image on the screen acting as a cool girl punk singer.

Name: Nick

Neighborhood: East Boston

School: MassArt

Plans for after college graduation: Travel cross-country

This year’s Convening is called After the Bell, and is about alternative spaces that contribute to teens’ education. How has the ICA contributed to your education? What does this space mean to you? What can teens get from spaces like the ICA that they might not get in school?

The ICA has provided me with an education in film that my high school could not. Being a part of the Fast Forward program was such an enriching experience that it influenced my major in college. This space has provided me with many opportunities that stem from challenges I wished to face. I was pushed to make ideas like “movie about pizza”—something that has substance and is interesting. Allowing me and encouraging me to bring ideas to life, no matter how ridiculous, the ICA has been a place where I have really developed as a person and understood what it’s like to create art.

What can young people stand to gain from regular exposure to making, seeing, and talking about art?

I think being regularly exposed to art allows young people to recognize art around them much more easily. Being encouraged to analyze something one might not fully understand or be comfortable with can help in so many other different aspects of life. I’m not saying everything is art, but it probably could be.

I did yoga with Whoopi Goldberg at the White House.

What are you most excited about for this year’s Teen Convening?

I’m excited to meet the other teens and learn about what their lives are like and see how they connect and relate to mine.

What is the weirdest or most memorable thing you’ve ever done at the ICA?

Because of the ICA, I was “punched in the face” in the same spot that Martin Sheen landed on when he was thrown off the roof in The Departed, and I did yoga with Whoopi Goldberg at the White House.

Name: Sienna

Hometown/neighborhood: Lower Mills

School: Boston Latin Academy

Plans for after graduation: College

This year’s Convening is called After the Bell, and is about alternative spaces that contribute to teens’ education. How has the ICA contributed to your education? What does this space mean to you? What can teens get from spaces like the ICA that they might not get in school?

The ICA has contributed the art education that my school didn’t provide. Without it, I would have no real connection to the art world. I’ve learned how to give tours, how to plan events, how to work in groups, and I even had the chance to do job shadowing! Learning about art careers and meeting artists is the best art education I could have. Museum spaces have always seemed exclusive and far removed, but the ICA encourages teens to jump into the museum space and feel comfortable in it. There’s something enriching about talking to an artist about their work, while you’re standing in the middle of piece or having artists talk to teens, as teens. Teens can definitely get an immersive look at the contemporary art world at the ICA. They can meet artists, see their work, and have in depth discussions about the pieces with the artist! They can make the museum space their own and remove the air of exclusivity that sometimes surrounds museums.

Learning about art careers and meeting artists is the best art education I could have.

What can young people stand to gain from regular exposure to making, seeing, and talking about art?

We can stand to gain a new perspective. As simple as that is, it’s really important. Interacting with art, especially if you don’t interact with it normally, can give you new ideas, different outlooks on life, and more creative ways to solve problems.

What are you most excited about for this year’s Teen Convening?

Meeting all the visiting teens, our presentations, and, of course, Teen Night!

What is the weirdest or most memorable thing you’ve ever done at the ICA?

Being a cherub for Yanira Castro’s Court/Garden performance.

ICA celebrates the tenth anniversary of its collection and signature waterfront building with an exhibition featuring works by Louise Bourgeois, Paul Chan, Eva Hesse, Cindy Sherman, Kara Walker, Andy Warhol, and many others.

Press are welcome to preview the exhibition on Tuesday, Aug 16 from 10 to 2 PM. Please contact Lisa Colli, lcolli@icaboston.org, if you need additional information, images, or would like to visit the exhibition on August 16.

The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston (ICA) celebrates its first decade of collecting and the tenth anniversary in its Diller Scofidio + Renfro-designed facility with the largest and most ambitious presentation of its collection to date. First Light: A Decade of Collecting at the ICA features over 100 works by seminal artists of the 20th and 21st centuries, including Louise Bourgeois, Nick Cave, Paul Chan, Marlene Dumas, Eva Hesse, Cindy Sherman, Kara Walker, and Andy Warhol. Occupying the entirety of the museum’s east galleries, First Light combines audience favorites with new acquisitions, many on view at the ICA for the first time.

This exhibition is organized by the ICA’s curatorial department under the leadership of Eva Respini, Barbara Lee Chief Curator. First Light: A Decade of Collecting at the ICA is on view from August 17, 2016 to January 16, 2017. During the first week of October, midway through the presentation, there will be a rotation of some of the sections (or “chapters”) enabling more of the collection to be showcased and new works and juxtapositions to be explored.

“First Light: A Decade of Collecting at the ICA provides a window onto contemporary artistic practice through the ICA collection. This series of simultaneous exhibitions reveals the driving visions of curators and collectors, the social, political, material, and aesthetic concerns of contemporary artists, and the history of ICA exhibitions over the past many years,” said Jill Medvedow, Ellen Matilda Poss Director. “The exhibition celebrates a monumental ten years at the ICA and marks a historic transformation in our community. We are very grateful to our generous supporters who have allowed us to grow the collection significantly and strategically.”

Conceived as a series of interrelated and stand-alone exhibitions, First Light is organized into thematic, artist-specific, and art-historical chapters that each tell a different story. The first section features three major highlights of the exhibition. These are:

- Paul Chan’s 2005 projected digital animation 1st

Light, created for the ICA, was one of the first works to enter the collection, and the inspiration for the exhibition’s title. This significant moving-image piece highlights the ICA’s aim to collect works of art in diverse media and by important contemporary artists with a critical voice. - Cornelia Parker’s Hanging Fire (Suspected Arson) (1999) is a favorite among visitors and the ICA’s first promised work. Parker’s first monographic exhibition was mounted at the original ICA facility in 2000.

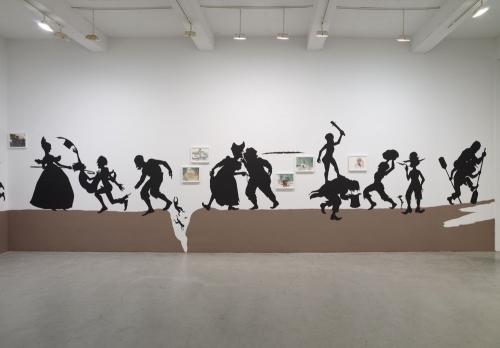

- Kara Walker’s newly acquired monumental cut-paper silhouette tableau, The Nigger Huck Finn Pursues Happiness Beyond the Narrow Constraints of your Overdetermined Thesis on Freedom – Drawn and Quartered by Mister Kara Walkerberry, with Condolences to The Authors (2010), is prominently displayed. On view for the first time at the ICA, the combination of materials—cut-paper silhouettes, wall paint, and framed works on paper—is unusual within Walker’s oeuvre, making the work a major addition to the collection.

Other highlights include groupings of work by artists held in-depth in the collection including Louise Bourgeois, Rineke Dijkstra with Nan Goldin, and a gallery dedicated to objects from The Barbara Lee Collection of Art by Women. To accommodate the breadth of stories within the collection, several chapters will switch out halfway through the exhibition’s run. The Barbara Lee Collection of Art by Women and Soft Power galleries (described below) will be on view through January 16, serving as anchors to the overall exhibition.

A new, multimedia web platform at icaboston.org accompanies the exhibition and features descriptions of the works, interviews with artists, and commentary by current and former ICA curators reflecting on works that entered the collection during their tenure. The content-rich microsite will launch in tandem with the exhibition.

“In ten years, the ICA has established a collection of great variety, ranging from historically significant work of figures such as Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois to the contemporary explorations of leading artists such as Kara Walker and Paul Chan,” said Eva Respini, Barbara Lee Chief Curator. “The work in First Light represents a broad range of art-making today by artists who explore the issues of our time.”

First Light explores a diversity of narratives from biography and material to feminism and appropriation in the following sections or chapters.

The Barbara Lee Collection of Art by Women

On view August 17, 2016–January 16, 2017

The Barbara Lee Collection of Art by Women is the cornerstone of the ICA’s growing collection. The collection includes artists working in diverse media who have made significant contributions to art over the past 40 years. This exhibition is arranged by various media and subject matters, highlighting the collection’s strength in works of sculpture and assemblage, as well as drawing and painting. Included are signature works by Marlene Dumas, Ellen Gallagher, Ana Mendieta, Cornelia Parker, Doris Salcedo, Kara Walker, among others, in addition to salient historical precedents set by figures such as Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois. Together, these works examine issues of the political, personal, and social body, and larger concepts of identity, all in distinct and thought-provoking ways. This section demonstrates the strength of the ICA’s expanding collection and how the collection engages in critical discourses in the arts as well as broader social and cultural contexts. The Barbara Lee Collection of Art by Women is organized by Eva Respini, Barbara Lee Chief Curator.

Soft Power

On view August 17, 2016–January 16, 2017

Formed by pliable materials including rope, thread, string, and fabric, the works in Soft Power derive their presence and power from, on the one hand, the seductive textures, structures, and surfaces of textiles, and on the other, the evocative social and cultural connotations these materials provoke. The smears and patterns of Kai Althoff’s gloss paint on fabric conflate painting and body in a surreal clothing-like fragment in Untitled (2004), while Alexandre Da Cunha’s BUST XXXV (2012) lurks like a floating figure, shrouded in its uncanny cover of mop and string. Sculptures by Josh Faught, Françoise Grossen, Charles LeDray, and Robert Rohm—crocheted, knotted, and sewn—variously lean against the wall, sprawl, pile on the floor, and hang to evoke the body by its covering, adornment, and poses only possible through their shared soft construction. Soft Power is organized by Dan Byers, Mannion Family Senior Curator.

Question Your Teaspoons

On view August 17–October 2, 2016

This exhibition explores the sphere of the domestic in the making and meaning of art. A counterpoint to such celebrated contexts as the artist’s studio and the public sphere, the home has often served artists, especially female artists, as a crucial site for the creation of their work. Artists in this exhibition derive inspiration from the objects, relationships, and aesthetics that surround them. Sherrie Levine, Doris Salcedo, and Diane Simpson reimagine mundane objects in their sculptural works; LaToya Ruby Frazier, Cindy Sherman, and Andy Warhol probe familial relations through their photographs; and Chantal Joffe and Mickalene Thomas offer striking paintings of intimate interior scenes. The title of this section is from a quote by Georges Perec, the great cataloguer of everyday life who challenged readers to scrutinize the ordinary. To “question your teaspoons” is to pay attention to—and bring new attention to—a quotidian thing, to study life in order to live it differently. Question Your Teaspoons is organized by Ruth Erickson, Associate Curator.

Rineke Dijkstra / Nan Goldin

On view August 17–October 2, 2016

The ICA has rich holdings of works by Rineke Dijkstra and Nan Goldin, two leading figures in contemporary photography with a keen interest in portraiture. Both artists have a history with the ICA: the museum hosted Goldin’s first solo museum exhibition in 1985 and one of Dijkstra’s first surveys in the United States in 2001. Referencing both the historical genre of portraiture and documentary-style photography, these artists expound upon these traditions in divergent and unique ways. Goldin’s bold images depict her loved ones and closest acquaintances caught in intimate moments. From the artist’s mother laughing to a drag queen lounging at home, her compositions are vibrant and rich, powerfully emotive, and full of psychological intent. Dijkstra’s stark portraits, on the other hand, present the subjects in heightened focus and repose, stripped bare of context. The artists subtly and overtly examine the shifting nature of identity and self. Goldin’s captures an instant within a broader narrative, expressing her subjects’ personal relationships or exploring their gender identities, while Dijkstra’s subjects, including new mothers and children growing into adolescence, are at the cusp of unpredictable chapters in their lives. These works, ultimately capturing everyday moments, encourage the viewers to intimately engage with the pictured subjects, and to seek out clues of their personal lives and character, reflecting our own searches for the extra in the ordinary and the thrill in the mundane. Rineke Dijkstra / Nan Goldin is organized by Jessica Hong, Curatorial Assistant.

The Freedom of Information

On view October 8, 2016–January 16, 2017

The Freedom of Information is a concise survey of artworks that employ strategies of appropriation, from repurposing and rephotographing mass-media images to referencing and copying objects from art history or American consumer culture. While key moments in the history of artistic appropriation (such as the readymade, collage, and montage) date back to the early 20th century, it was in the 1970s and 80s that the critical terms of these practices were established in the context of a new generation of influential artists. The Freedom of Information traces a particular lineage of appropriation that accounts for the variety of its different models. Here, an intergenerational group of artists “take” materials from sources such as books, postcards, television, or art-specific contexts, manipulating them using cameras, printers, or scanners. The works in The Freedom of Information reveal that while such forms of repetition are historically rooted, appropriation remains a critically urgent means with which to address a culture saturated with images. Artists in The Freedom of Information include: Dara Birnbaum, Carol Bove, Anne Collier, Gilbert & George, Leslie Hewitt, Louise Lawler, Sherrie Levine, Cady Noland, Thomas Ruff, Sara VanDerBeek, Charline von Heyl, Kelley Walker, and Andy Warhol. The Freedom of Information is organized by Jeffrey De Blois, Curatorial Assistant.

Louise Bourgeois

On view October 8, 2016–January 16, 2017

One of the most influential artists of the 20th century, Louise Bourgeois worked for more than 70 years in a variety of materials—including wood, bronze, marble, steel, rubber, and fabric—to create a distinctive and expansive body of work. Blending abstraction and figuration, Bourgeois delved into the struggles of everyday life to create personally cathartic objects that reference the body, sexuality, family, trauma, and anxiety. Since the ICA’s exhibition Bourgeois in Boston (2007-08), the museum has acquired a number of her works; this selection brings together sculptures and works on paper to consider her use of framing devices. From the enclosures and doors in her large-scale cell sculptures to vitrines, borders, and platforms, the partition of space recurs in Bourgeois’ work. These “frames” serve various ends, but each articulates a kind of boundary — an inside and an outside, an object and its space, the very divisions Bourgeois so famously disrupted in her life’s work. Louise Bourgeois is organized by Ruth Erickson, Associate Curator.

First Light: A Decade of Collecting at the ICA is sponsored by

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Additional support is generously provided by Fiduciary Trust Company, Chuck and Kate Brizius, Katie and Paul Buttenwieser, Karen and Brian Conway, the Robert E. Davoli and Eileen L. McDonagh Charitable Foundation, Jean-François and Nathalie Ducrest, Cynthia and John Reed, and Charles and Fran Rodgers.

Sonia Almeida, Jennifer Bornstein, Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel, and Lucy Kim have been named the recipients of the 2017 James and Audrey Foster Prize Exhibition, the museum announced today. In media including painting, sculpture, printmaking, film, and video, and exploring a range of themes and subjects, each of the artists engage the human body with a tactile approach to its cultural, psychological, and historical resonances. Each of the artists will present a major work, or group of works, on view for the first time in Boston. The exhibition is organized by Dan Byers, Mannion Family Senior Curator, with Jeffrey De Blois, Curatorial Assistant, and will be on view at the ICA from Feb. 15 through July 9, 2017.

“This year’s James and Audrey Foster Prize Exhibition shines a light on a selection of established Boston-based artists working at a national and international level, but whose work has only received limited exposure here at home,” said Jill Medvedow, Ellen Matilda Poss Director of the ICA. “We are grateful to Jim and Audrey for this opportunity to share such exceptional work with our audiences.”

“We are very pleased to congratulate the 2017 recipients of the Foster Prize. Their work demonstrates the creativity, strength, and talent of Boston’s robust art community,” said James Foster, Chair of the ICA Board of Trustees and Chairman, President & Chief Executive Officer of Charles River Laboratories.

Central to the exhibition, this iteration of the James and Audrey Foster Prize features a new program, Foster Talks, enabling audiences to engage more deeply in the work and practice of the Prize winners. Once a month over the course of the exhibition, in a space in the exhibition galleries, each artist will present their work and invite an important writer, artist, performer, researcher, or other cultural producer who has influenced their artwork, or whose own work resonates with the artist’s. The conversations will be followed by a free reception, open to the public. The Foster Talks will connect questions around contemporary art to a broad range of cultural, intellectual, and political issues, creating relationships between art and different fields. Through the Foster Talks, the ICA will welcome an expanded cultural community to form around the exhibition, animating the galleries throughout the duration of the exhibition.

Images are available upon request.

Profiles of the 2017 Foster Prize Artists

Sonia Almeida was born in Lisbon, Portugal, and lives in Arlington, MA. Almeida received a B.A. from Faculdade de Belas Artes da Universidade de Lisboa and a M.F.A. from Slade School of Fine Art, University of London. She has received numerous awards and grants, including a Pollock-Krasner Foundation grant and an Artist Fellowship from the Massachusetts Cultural Council. Her work has been widely exhibited at institutions nationally and internationally, including the MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge; Culturgest, Portugal; Serralves Museum, Portugal; and Witte de With, Netherlands.

Jennifer Bornstein was born in Seattle and lives in Cambridge, MA. Bornstein received a B.A. from the University of California, Berkeley, and a M.F.A. from the University of California, Los Angeles, before participating in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Independent Study Program. She has received numerous awards and grants, including a DAAD Berliner Künstlerprogramm fellowship and a Pollock-Krasner Foundation grant. Her work has been widely exhibited at institutions nationally and internationally, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Lucien Castaing-Taylor was born in Liverpool, UK, and Véréna Paravel was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland; they are based in Cambridge, MA, and Paris, France. In 2006, Castaing-Taylor founded the Sensory Ethnography Lab (SEL), an experimental film center at Harvard University whose collaborative output in a variety of media—including film, video, phonography, and photography—innovatively draws from the fields of aesthetics and ethnography. Castaing-Taylor’s work is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the British Museum, London, and has been exhibited at Tate, London; Centre Pompidou, Paris; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Whitechapel Gallery, London; and Institute of Contemporary Arts, London. Paravel’s films have won Best First Feature and the Best First Feature Jury award at the Festival del Film Locarno and the Punto de Vista Award for Best Film. Foreign Parts (with J.P. Sniadecki, 2010) was a New York Times Critics’ Pick. Castiang-Taylor, Paravel, and the Sensory Ethnography Lab were included in the 2014 Whitney Biennial.

Lucy Kim was born in Seoul, South Korea, and lives in Cambridge, MA. She received a B.F.A. from the Rhode Island School of Design and a M.F.A. from the Yale School of Art. She attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and the MacDowell Colony, and is the recipient of the Carol Schlosberg Memorial Prize and the Ellen Battell Stoeckel Fellowship from Yale, as well as the Boston Artadia Award. She is a founding member of the collaborative kijidome, and is currently Lecturer in Fine Arts at Brandeis University. Her work is included in the collection of the Kadist Foundation in Paris, among others.

About the James and Audrey Foster Prize

The James and Audrey Foster Prize is key to the ICA’s efforts to nurture and recognize exceptional Boston-area artists. First established in 1999, the James and Audrey Foster Prize (formerly the ICA Artist Prize) expanded its format when the museum opened its new facility in 2006. James and Audrey Foster, passionate collectors and supporters of contemporary art, endowed the prize, ensuring the ICA’s ability to sustain and grow the program for years to come.

Your guide to a new season of music, dance + film at the ICA featuring Bill T. Jones, Kara Walker, Meredith Monk + more!

Tickets are now on sale for a packed season of music, dance, art, and more starting in September:

- the return of legendary choreographer Bill T. Jones to the ICA stage

- a free talk by renowned artist Kara Walker

- five Boston premieres from celebrated choreographer Annie-B Parson

- a singular evening of music and poetry by Meredith Monk and Anne Waldman

- RY X’s lush melodies and raw, emotional lyrics

-

an exhibition celebrating the museum’s first decade of collecting featuring more than 100 works by Cindy Sherman, Andy Warhol, Nan Goldin, Kara Walker, Louise Bourgeois, among others

-

and more!